What Are Stablecoins And How Do They Work?

*Forward the Original Title ‘A Guide To Stablecoins: What Are Stablecoins And How Do They Work?’

Introduction

This article is the first in a four-part series that seeks to explain the intricacies of the stablecoin landscape. The mechanics of stablecoins are complex, and no comprehensive educational resource currently consolidates the mechanics, risks, and tradeoffs associated with various stablecoins. This series aims to fill that gap. Based on issuer documentation, onchain dashboards, and project team explanations, this guide offers investors a framework for evaluating stablecoins.

Part One of our four-part series introduces stablecoins, including their designs and history. Each of the other three articles focuses on one of the three dominant categories of stablecoins:

- Majority Fiat-Backed Stablecoins (Part II)

- Multi-Collateral-Backed Stablecoins (Part III)

- Synthetic Dollar Models (Part IV)

Each of those articles outlines the management of stablecoin reserves, the opportunities surrounding yield and incentives, the ease of token access and native integrations, and the resilience of the tokens based on governance and compliance. Each article also considers the external dependencies and peg mechanisms that determine whether stablecoins are likely to retain parity during periods of market stress.

Part Two of this series begins with Majority Fiat-Backed stablecoins, the dominant and most straightforward design. Parts Three and Four evaluate more complex stablecoin types, Multi-Collateral-Backed stablecoins and Synthetic Dollar Models. These in-depth analyses offer investors a comprehensive framework for understanding the assumptions, tradeoffs, and exposures associated with each type of stablecoin.

Please enjoy Part One of our Series.

Stablecoins: Crypto’s ChatGPT Moment

The emergence of stablecoins was a pivotal moment for the crypto industry. Governments, corporations, and retail users now recognize the advantages of streamlining the global financial system with blockchain technology.1 Crypto’s evolution has proven that blockchains can serve as viable alternatives to traditional financial rails, enabling the digitally native, global, real-time transfer of value—all through one unified ledger.

That recognition, along with the global demand for US dollars (USD), has created a unique opportunity to accelerate the convergence of crypto and traditional finance. Stablecoins are at the intersection of that convergence, both for legacy institutions and for governments. Between the two, the key forces driving stablecoin adoption are:

- Legacy institutions seeking to remain relevant as the global payments landscape modernizes.

- Governments seeking access to new debt holders to finance their deficits.

Though motivated by different objectives, both governments and incumbent financial institutions know that they must embrace stablecoins or risk losing influence as the financial paradigm shifts. Recently, ARK’s Director of Digital Assets Research, Lorenzo Valente, published a detailed paper on this topic—Stablecoins Could Become One Of The US Government’s Most Resilient Financial Allies.2

Retail adoption also has gained momentum now that stablecoins are no longer solely niche tools for crypto traders. Instead, they have become integral to cross-border remittances, DeFi (Decentralized Finance), and the primary means of dollar exposure in emerging markets with limited access to stable fiat currencies. That said, despite their growing utility and increased adoption, for many investors the complex structures and mechanisms that underpin the stablecoin landscape are opaque.

Understanding Stablecoins

A stablecoin is a tokenized claim, issued on a blockchain, entitling holders to one dollar of some asset, either onchain or offchain. Backed by collateral reserves that are managed through traditional custodians or automated onchain mechanisms and stabilized through peg-arbitrage, stablecoins are designed to absorb volatility and preserve parity with a target asset, typically USD or another fiat currency.

The heavy skew toward USD denominated stablecoins is a byproduct of the product-market fit stablecoins have found in giving synthetic dollar exposure to dollar-scarce markets. By combining the stability of the US dollar with the cost efficiency and 24/7 accessibility of blockchains, stablecoins have emerged as both a compelling medium of exchange and a reliable store of value. That dynamic has been especially powerful in markets long plagued by currency instability and limited access to US bank accounts. In that context, stablecoins effectively serve as digital onramps into dollar exposure, which is reflected by the regions with the fastest growing onchain activity in 2025: APAC (Asia Pacific), Latin America, and Sub-Saharan Africa.3

Additionally, Stablecoins have transformed the growth of crypto, especially decentralized finance (DeFi), by introducing a liquid, low-volatility unit of account. Without stablecoins, onchain markets would have been forced to denominate trades in volatile assets like bitcoin (BTC), ether (ETH), or solana (SOL), not only exposing users to price risk but also lessening the practical use of decentralized finance (DeFi).

By offering the stability of dollar-pegged assets onchain, stablecoins increase capital efficiency by improving both price discovery and onchain trade settlements across DeFi protocols. Such stability and reliability are critical to the core infrastructure upon which these new financial markets depend. As a result, the specific peg-mechanisms and reserve architecture that maintain those qualities are important to their resilience, especially during periods of market stress.

Asset Or Debt Instrument? Stablecoin Design Yields Tangible Differences

The underlying mechanisms and reserve architectures of stablecoins directly influence their economic and legal behavior. Different architectures come with distinct advantages and disadvantages in terms of regulatory compliance, censorship resistance, degree of crypto-native design, and/or control and stability. They also determine how a stablecoin functions and what risks, behaviors, and limitations a holder should expect. Such subtleties raise key questions about how a stablecoin should be understood—whether specific stablecoin types should be regarded as assets or debt instruments, as one example.

In this context, a stablecoin can be thought of as an “asset” when the holder has direct legal ownership of the stablecoin or its backing reserves, thereby retaining enforceable rights even in issuer insolvency. A stablecoin acts more like a “debt instrument” when the issuer retains legal ownership of reserves and the holder has only a contractual claim, effectively as an unsecured creditor. The distinction is determined by the issuer’s legal design and how the reserve custody is structured.

The classification depends primarily on who controls the reserves that back the token and whether that party is legally obligated to honor redemptions. While most issuers might intend to fulfill redemptions even under stress, without a clear legal obligation or user-controlled reserves, the token functions more like a debt instrument. This distinction determines whether holders retain enforceable rights to the underlying collateral in a worst-case scenario.

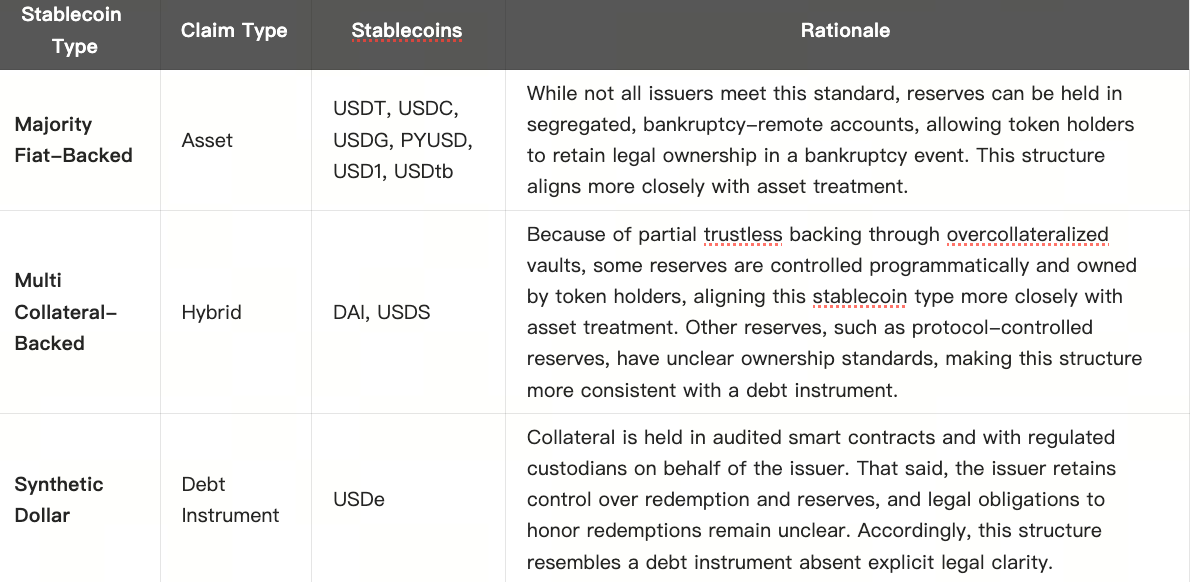

The table below outlines how stablecoin types differ based on this classification.

ote: Because stablecoins are novel, majority fiat-backed issuers with segregated, bankruptcy-remote accounts have disclosed the lack of legal precedent that would guarantee holders entitlement to the reserve assets, even with the proper legal structure. In Circle’s S-1, for example, the “Treatment of Reserve Assets” section refers to this complicated situation. Source: ARK Investment Management LLC, 2025. For informational purposes only and should not be considered investment advice or a recommendation to buy, sell, or hold any particular security or cryptocurrency.

Such structures are often deliberate, based on the region, target market, or specific utility for which the stablecoin is optimized. Even so, the variance in legal structures can introduce subtle differences that translate into meaningful tradeoffs to the token holder. Notably, this is one of many interesting examples in which both intentional and non-intentional architectural differences can give rise to meaningful consequences for the stablecoin and the investor.

Past Stablecoin Failures Were Closely Connected To Stablecoin Design

Some problematic events in the past entailed the depegging of stablecoins from the selected fiat currency during a crisis. Those events are poignant reminders that design differences carry real consequences, particularly during periods of market stress. Indeed, each stablecoin type has experienced failures reflective of their architectural deficiencies and design choices. Below, I discuss some of the most pronounced stablecoin failures, each associated with each of the three types, respectively. My discussion will set the stage for an in-depth analysis of each type of stablecoin—Majority Fiat-Backed, Multi-Collateral-Backed, and Synthetic Dollar Models—in Parts II, III, and IV of this series.

The Collapse Of SVB, Silvergate, And Signature

In March 2023, the collapse of three crypto-focused US banks—Silvergate, Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), and Signature Bank, highlighted that fiat-backed stablecoins were and are exposed to traditional banking infrastructure. The collapse began as Silvergate—already strained by large holdings of long-term Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities that imploded as the US Federal Reserve (Fed) jacked interest rates up at an unprecedented rate—lost access to Federal Home Loan Bank (FHLB) support. Silvergate had to satisfy mounting withdrawals by selling assets at steep losses, accelerating its downfall and undermining confidence in both SVB and Signature, which then failed.

When Circle disclosed that it had a $3.3 billion exposure to SVB, its stablecoin, USDC, depegged to $0.89 per $1.00, causing panic across DeFi and centralized markets until the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) guaranteed all deposits. Within days, USDC restored its peg. Nonetheless, the shock ripped across stablecoins—including DAI which, heavily collateralized with USDC, also depegged. Later, Circle diversified its banking partners, but the crisis left lingering concerns about the fragility of the linkages between stablecoins and banks.4

TerraLuna’s Algorithmic Implosion

In early 2022, Terra was a leading Layer 1 ecosystem built around its algorithmic stablecoin, UST, and its native token, Luna. Anchor, a lending protocol built on Terra that paid a guaranteed 19.5% yield to depositors, was the main driver of capital into the TerraLuna ecosystem. UST maintained its peg through arbitrage: 1 UST could redeem $1 of Luna, with UST issuance burning Luna and redemptions minting it. Although Terra’s leadership later added both BTC (bitcoin) and other crypto reserves, they never exceeded ~20% of UST supply, leaving the system largely unbacked. At its peak, TerraLuna had attracted billions of dollars, despite limited external use cases and an unsustainable yield funded largely by Terra subsidies instead of organic borrowing demand.

When markets turned and Luna’s price fell below the outstanding value of the UST supply, the redemption mechanism gave way. In May 2022, a depegging of UST sparked a mass exodus. Terra capped redemptions, pushing more selling into secondary markets. As redemptions resumed, Luna hyperinflated its supply to absorb fleeing capital, soared from hundreds of millions to trillions of tokens, and collapsed in price. BTC reserves failed to stem the spiral. Within days, more than $50 billion from the combined market capitalization of UST and Luna was wiped out.5

DAI’s Black Thursday

On March 12, 2020—“Black Thursday” in the MakerDAO (now Sky Protocol) community—sharp price declines and Ethereum congestion triggered a systemic failure in DAI’s liquidation mechanism. As ETH fell more than 40%, hundreds of vaults dropped below collateralization thresholds. Typically, liquidations had been resolved through onchain auctions in which “keepers” bid DAI for collateral. On Black Thursday, however, high gas fees and delayed oracle updates prevented many bids, giving speculators and opportunistic actors the chance to win collateral vaults with near zero dollar offers. More than 36% of the liquidations cleared at 100% discounts, creating a 5.67 million DAI deficit and wiping out many vault owners.

Adding insult to injury, as borrowers rushed to buy DAI and repay debt, DAI depegged and appreciated. Normally, arbitragers would mint new DAI to meet demand, but this time network congestion, volatile prices, and oracle delays became obstacles. Liquidations and minimal issuance created a supply shock as demand soared, pushing the peg higher. MakerDAO responded with a debt auction and minted Maker (MKR), the now deprecated utility token of MakerDAO, to recapitalize the protocol. The crisis exposed DAI’s vulnerabilities in liquidation design and stablecoin stability under stress, prompting major reforms to Maker’s liquidation engine and collateral model.6

Stablecoin Design Matters

The collapse of Silvergate, SVB, and Signature Bank, TerraLuna’s algorithmic implosion, and DAI’s Black Thursday serve as important reminders that stablecoin architecture matters. Those crises underscore how architectural design choices shape resilience and risk. TerraLuna’s collapse surfaced the structural fragility of fully algorithmic stablecoins, demonstrating that systems without sufficient collateral or genuine economic utility are inherently unstable and prone to collapse under stress.

In contrast, the depeggings of USDC and DAI, while concerning, were temporary and catalyzed meaningful reforms in both ecosystems. Circle enhanced the transparency of its reserves and strengthened its banking relationships following the SVB crisis, while MakerDAO (Sky Protocol) not only restructured its collateral mix to include more real-world assets (RWAs) but also upgraded its liquidation mechanism to prevent cascading failures.

Tying these events together is the way each exposed the flaws respective to its stablecoin type and the specific conditions that are most damaging to that type. Understanding how these architectures have evolved in response to their failures is important context for evaluating stablecoin design choices and differences today. Not all stablecoins are susceptible to the same risks; nor are they all optimized for the same purposes. Both outcomes stem from their respective underlying architectures. Recognizing that fact is essential to knowing where a stablecoin’s vulnerabilities lie and how best to use it.

Conclusion

In this article, I have introduced stablecoins and argued that stablecoin design matters. In Parts II-IV of this guide, I will explore each of the three dominant types of stablecoins: Majority Fiat-Backed, Multi-Collateral Backed, and Synthetic Dollar Models. Each embodies differences in resilience and tradeoffs that can be as important as its utility or user experience. The distinctive design, collateral, and governance characteristics of each type—and of the stablecoins themselves—are critical drivers of their respective risks and the token behaviors their holders should expect.

Disclaimer:

- This article is reprinted from [ARK]. Forward the Original Title ‘A Guide To Stablecoins: What Are Stablecoins And How Do They Work?’. All copyrights belong to the original author [Raye Hadi]. If there are objections to this reprint, please contact the Gate Learn team, and they will handle it promptly.

- Liability Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not constitute any investment advice.

- Translations of the article into other languages are done by the Gate Learn team. Unless mentioned, copying, distributing, or plagiarizing the translated articles is prohibited.

Related Articles

In-depth Explanation of Yala: Building a Modular DeFi Yield Aggregator with $YU Stablecoin as a Medium

What is Stablecoin?

Top 15 Stablecoins

A Complete Overview of Stablecoin Yield Strategies

Stripe’s $1.1 Billion Acquisition of Bridge.xyz: The Strategic Reasoning Behind the Industry’s Biggest Deal.