The Big Dangers of Big Bubbles with Big Wealth Gaps

While I am still an active investor hooked on the investing game, at this stage in my life, I am also a teacher trying to pass along what I’ve learned about how reality works and the principles that helped me deal with it well. Since I have been a global macro investor for over 50 years, and learned a lot of lessons from history, naturally a lot of what I pass along is about that.

This note is about:

- The important difference between wealth and money, and

- how that drives bubbles and busts, and

- how that dynamic, accompanied by big wealth gaps, could prick the bubble and lead to a bust that is socially and politically disruptive as well as financially disruptive.

It is important to understand the difference between wealth and money and the relationship between them, most importantly: 1) how bubbles occur when the amount of financial wealth becomes very large relative to the amount of money, and 2) how bubbles burst when there is a need for money that leads to the selling of wealth to get money.

This very basic, simple-to-understand concept about the mechanics of how things work is not well understood but has helped me a lot in my investing.

The main principles to know are that:

- Financial wealth can be created very easily and doesn’t represent its true value;

- financial wealth is of no value unless converted into money to spend; and

- converting financial wealth into money that can be spent requires selling it (or collecting its yield), which is what typically turns bubbles into busts.

Regarding “financial wealth can be created very easily and doesn’t represent its true value,” for example, nowadays if a founder of a startup sells shares in a company—let’s say $50 million worth—and values the company at $1 billion, then the seller has become a billionaire. This is because the company is worth $1 billion even though there is nowhere near $1 billion behind that wealth number. Similarly, if buyers of a publicly traded stock buy a few shares from sellers at a particular price, all shares are valued at that price, so by valuing all shares at that price you can determine the amount of wealth that exists in that company. Of course, these companies might not really be worth those valuations, as assets are only worth what they can be sold for.

Regarding “financial wealth is essentially worthless unless converted into money,” this is because wealth can’t be spent but money can.

When there is a lot of wealth relative to the amount of money, and those with wealth need to sell it to get money, the third principle applies: “converting financial wealth into money that can be spent requires selling it (or collecting its yield), which is what typically turns bubbles into busts.”

If you understand these things, you can understand how bubbles are created and how they burst into busts, which will help you anticipate and navigate bubbles and busts.

It’s also important to know that while both money and credit can be used to buy things, a) money settles the transactions, whereas credit creates debt that requires one to get money in the future to settle the transaction, and b) credit is easy to create, while money can only be created by the central bank. While one might think that one needs money to buy things, that’s not entirely true because one can buy things with credit, which creates debt that needs to be paid back. That’s typically what bubbles are made of.

Now, let’s look at an example.

While throughout history all bubbles and busts worked in essentially the same way, I will use the 1927-29 bubble and the 1929-33 bust as examples. If you think mechanistically about how the bubble of the late 1920s and the bust and the depression of 1929-33 worked and what President Roosevelt did to relieve the bust in March of 1933, you will see how the principles I just described worked.

Where did all the money come from to finance all the stock buying that made the stock market go up so much to make the bubble, and what made it a bubble? Common sense tells you that if there were a limited supply of money in existence and everything needed to be bought with money, then buying anything involves taking money out of something else. That something else probably would go down in price because of the selling, and the item being purchased would go up in price. However, it wasn’t money—it was credit then (e.g., in the late 1920s), always, and now, and credit can be created without money to buy stocks and other things that made the bubble. The dynamic then, which is the most classic dynamic, was that credit was created and borrowed to buy the stocks, which created debt that had to be paid back, so when the money needed to service the debt was greater than the money produced by the stocks, the financial assets had to be sold, which caused them to go down in price, and the bubble dynamic worked in reverse to make the bust dynamic.

The general principle for how these dynamics drive bubbles and busts is that:

When financial asset buying is financed by a lot of credit growth and the amount of wealth rises relative to the amount of money (so that there is a lot more wealth than there is money), that creates a bubble, and when wealth needs to be sold to get money, that creates a bust. For example, in the 1929-33 period, stocks and other assets had to be sold to pay the debt service on the debts that had been used to buy them, so the bubble dynamic worked in reverse. Naturally, the more borrowing and buying of stocks, the more they did well, and the more people wanted to buy them. These buyers didn’t have to sell anything to buy them because they could buy them with credit. The more they did that, the more credit became tighter and interest rates rose, both because the demand to borrow was so strong and because the Fed let interest rates rise (i.e., it tightened monetary policy). When the borrowing needed to be paid back, the stock had to be sold to get the money to service the debt, so prices fell, debt defaults happened so collateral became worth less, the availability of credit shrank, the bubble turned into a self-reinforcing bust, and a depression followed.

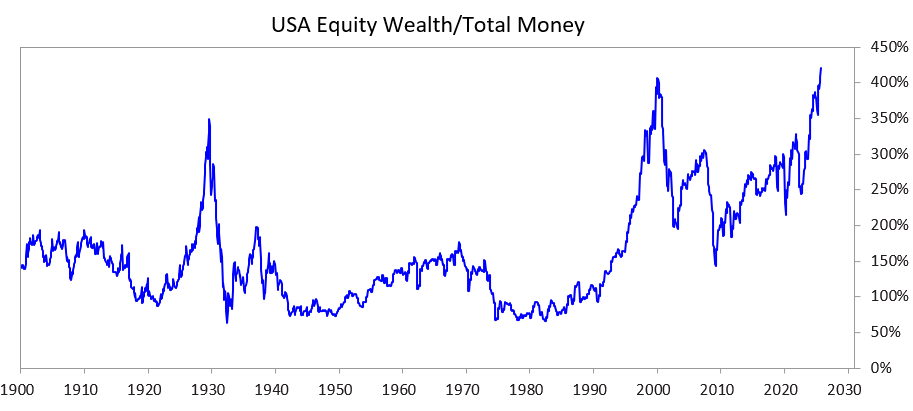

To explore how that dynamic accompanied by big wealth gaps could prick the bubble and lead to a bust that will be socially and politically disruptive as well as financially disruptive, I examined the chart below. It conveys what the wealth/money gap has looked like in the past and looks like now. It shows the total value of equities relative to the total value of money.

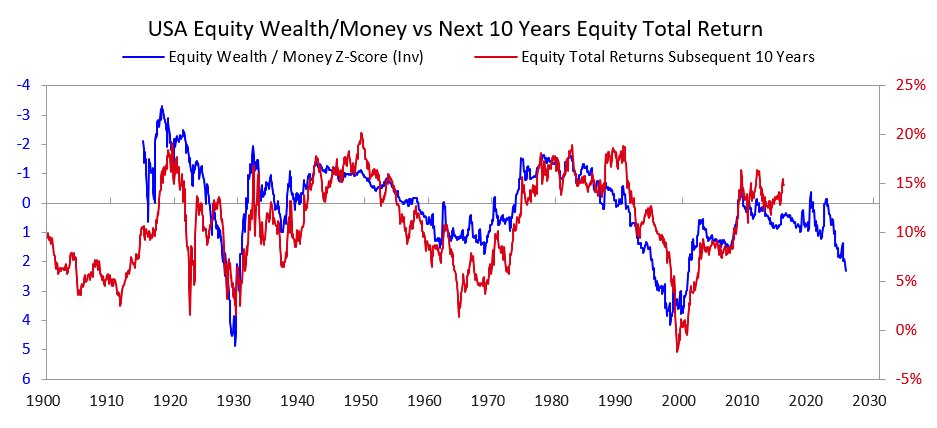

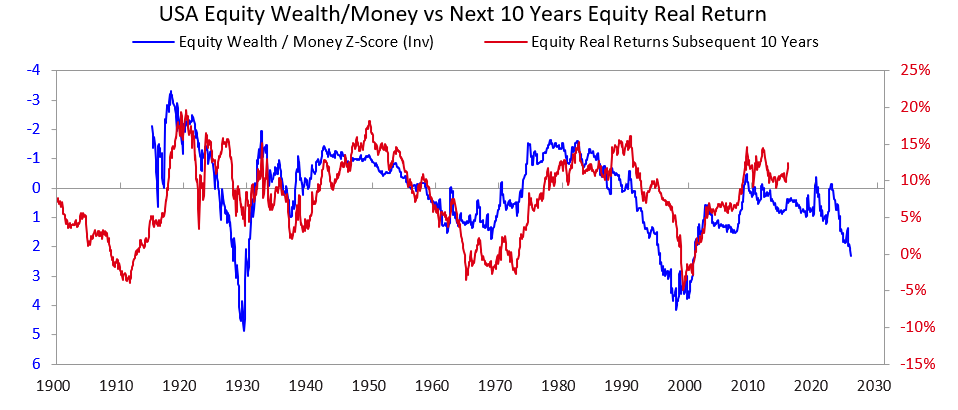

The next two charts show how that reading is an indicator of the next 10 years’ nominal and real returns. These charts speak for themselves.

When I listen to people trying to assess whether a stock or the stock market is in a bubble by trying to figure out whether the companies will end up becoming profitable enough over time to provide an adequate return for the current prices, I think to myself that they don’t understand the bubble dynamic. While what an investment will earn is of course important over time, it isn’t the primary reason bubbles burst. Bubbles don’t burst because people wake up one morning and determine that there won’t be enough revenue and profits to justify the price. After all, whether or not there will be enough revenue and profits to provide a good ROI won’t be known for many years, typically decades. The principle to keep in mind is that:

Bubbles pop because the money flowing into the asset begins to dry up and the holders of stocks and/or other wealth assets need to sell them to get money for some purpose (most commonly for debt service payments).

What typically comes next?

After bubbles pop, when there isn’t enough money and credit to meet financial asset holders’ needs, the markets and economy decline, and internal social and political disruptions typically increase. That is especially true if there are large wealth gaps because they intensify the differences and the anger between those of the rich/right and those of the poor/left. In the 1927-33 case that we are looking at, that dynamic caused the Great Depression that led to great internal conflict, particularly between the rich/right and the poor/left. This dynamic led to President Hoover getting thrown out of office and the election of President Roosevelt.

Naturally, when bubbles burst and there are market and economic declines, these things lead to big political changes, big deficits, and big debt monetizations. In the 1927-33 example, the market and economic declines happened in 1929-32, the political changes came in 1932, and these things led to President Roosevelt’s administration running huge budget deficits in 1933.

His central bank printed a lot of money, which devalued money (e.g., in relation to gold). Devaluing money in this way alleviated the money shortage and a) helped the systemically important debtors that were being squeezed make debt service payments, b) raised asset prices, and c) stimulated the economy. Leaders who come to power in moments like this also typically make many shocking fiscal changes that I don’t have the space here to explain in detail, but I can say that these times generally lead to great conflicts and great transitions of wealth. In the Roosevelt case, these circumstances led to many big fiscal policy changes to shift wealth from the top to the rest (e.g., raising the top marginal income tax rate to 79% from 25% in the 1920s, raising estate and gift taxes sharply, and funding big increases in social programs and subsidies). It also led to great conflicts both within countries and between countries.

That is the classic dynamic. Throughout history, it has led too many leaders and too many central banks to name to do the same things too many times in too many countries over too many years for me to recount here. By the way, before 1913, the US didn’t have a central bank, and the ability of the government to print money didn’t exist, so bank defaults and deflationary depressions were more typical. In either case, bond holders do badly, and gold holders do well.

But while the 1927-33 example is a good one of what the classic bubble-bust cycle looks like, that case is one of the more extreme ones. You can see the same dynamic in what led President Nixon and the Fed to do the exact same thing in 1971 and led virtually all the other bubbles and busts to happen (e.g., 1989-90 in Japan, the 2000 dot-com bubble, etc.). These bubbles and busts have a number of other typical characteristics (like the market being very popular with unsophisticated investors who are drawn in by the popularity, buy in a leveraged way, lose a lot of money, and get angry).

This dynamic has worked this way for thousands of years when these conditions existed (i.e., when the demand for money became greater than the supply of it). Wealth had to be sold to get the money, bubbles popped, and defaults, money printing, and bad economic, social, and political things happened. In other words, that imbalance between the amount of financial wealth and money and the turning in of financial wealth (especially debt assets) for money is what has always caused runs in banks, both private banks and government-controlled central banks. These runs led either to defaults (which mostly happened prior to the creation of the Federal Reserve) or the creation of money and credit by the central bank to be given to those who were too important to be allowed to fail so that they could service their loans and not fail.

So, keep in mind:

When the promises to deliver money (i.e., debt assets) are far greater than the amount of money that exists, and there is a need to sell financial assets to get money, watch out for a bubble bursting and be sure you’re protected (e.g., don’t have significant credit exposures and own some gold). If that happens when there are big wealth gaps, watch out for big political and wealth changes and be sure to be protected against them.

While interest rate increases and tightenings of credit have been the most common causes of the selling of assets to get the money that was needed, any reason that creates a need for money—for example, wealth taxes—and the selling of financial wealth to get that money could lead to that dynamic.

When there is a big wealth/money gap at the same time as there is a big wealth gap, that should be viewed as a very risky set of circumstances.

From the 1920s Until Now

(You can skip this if you don’t care to read a quick description of how we got from the 1920s to now.)

While I touched on how the 1920s bubble led to the 1929-33 bust and depression, to quickly bring you up to date, that bust and the resulting depression led to President Roosevelt’s 1933 default on the US government’s promise to give the then hard money (gold) at the promised price. The government printed a lot of money, and gold rose by approximately 70%. I will skip going over how the 1933-38 reflation led to the 1938 tightening; how the “recession” of 1938-39 created the economic and leadership ingredients that, together with the geopolitical dynamic of the German and Japanese rising powers challenging the British and American leading powers, led to World War II; and how the classic Big Cycle dynamic took us from 1939 to 1945 (when the old monetary, political, and geopolitical orders broke down and the new ones were set up).

I won’t dive into why, but I will note that these things led to the US becoming very rich (it held two-thirds of the world’s money, which was then gold) and powerful (it produced half of world GDP and was the dominant military power). So, when the new monetary order was set out in the Bretton Woods agreement, it continued to base money on gold, the dollar was linked to gold (other countries could use the dollars they acquired to buy gold at $35 an ounce), and other countries’ currencies were linked to gold. Then, between 1944 and 1971, the US government spent a lot more than it took in from taxes, so it borrowed a lot, which it sold as debt, thus creating a lot more claims on gold than there was gold in the central bank. Seeing this, other countries started turning their paper money in for gold. This made money and credit undesirably tight, so President Nixon did the same thing in 1971 as President Roosevelt did in 1933, again devaluing fiat money relative to gold, and the price of gold soared. Suffice it to say that from then until now, a) government debt and debt service costs rose sharply relative to the tax income needed to service the government debt (especially in the 2008-12 period following the 2008 global financial crisis and since 2020, when there was the COVID financial crisis); b) income and values gaps grew to where they are now, which is very large, so we now have irreconcilable political differences; and c) the stock market is probably in a bubble boosted by the credit-, debt-, and creativity-supported speculations on new technologies.

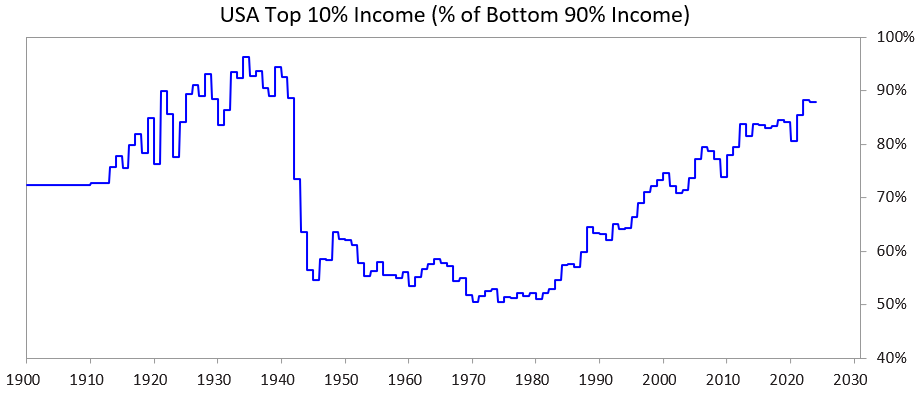

The chart below shows the income shares of the top 10% relative to the bottom 90%—you can see that they are very large today.

Where We Are Now

The United States and all the other countries’ governments that have overborrowed and are democratically run are now in a position where they a) can’t increase their debts as they did before, b) can’t raise taxes enough, and c) can’t cut spending enough to prevent running deficits and increasing their debts. They are stuck.

To explain in more detail:

They can’t borrow enough because there isn’t adequate free-market demand for their debt. (This is because they are already overindebted, and the holders of their debt already have too much of it.) Also, international holders of debt assets of other countries (e.g., China) worry that the war-like conflicts could lead to them not being paid back, so their buying of bonds is waning and they are shifting their debt assets into gold.

They can’t raise taxes enough because if they raise taxes on the top 1-10% of people (who have most of the wealth), a) these people will leave, taking their tax paying with them, or b) the politicians will lose the support of the top 1-10% (which is important to fund expensive campaigns), or c) they will pop the bubble.

And they can’t cut spending and cut benefits enough because that’s politically and, perhaps, morally unacceptable, especially as those cuts will disproportionately affect those in the bottom 60%…

…so they are stuck.

For these reasons, all democratic governments in countries that have big debt, big wealth, and big values differences are in trouble.

Given these conditions, the way the democratic political system works, and what people are like, politicians are promising quick fixes, failing to deliver satisfactory results, and are quickly being thrown out of office and replaced by new politicians who are promising quick fixes, failing, and being replaced, and so on. That’s why the UK and France, which have systems that can replace leaders quickly, have each had four prime ministers in the last five years.

Said differently, we are now seeing the classic pattern that is typical at this stage in the Big Cycle. This dynamic is very important to understand and should now be obvious.

Meanwhile, the stock market and wealth boom are highly concentrated in the top AI-related stocks (e.g., the Mag 7) and with a small group of very rich people, and AI is replacing people and increasing both the wealth/money gap and the wealth gap between people. Having seen this dynamic many times in history, I think that there is a significant likelihood of a big political and social backlash that will, at a minimum, significantly change wealth distribution and, at a maximum, could produce severe social and political disorder.

Let’s now look at how this dynamic and the big wealth gaps together are causing problems for monetary policy and could lead to wealth taxes that would prick the bubble and lead to a bust.

What the Numbers Look Like

I will now compare those in the top 10% of wealth and incomes with those in the bottom 60% of wealth and incomes. I picked the bottom 60% because that constitutes the majority of people.

In brief:

- The wealthiest (top 1-10%) have greatly more wealth, income, and stock ownership than most people (the bottom 60%).

- Most of the wealth of those who are the wealthiest is coming from their wealth increasing in value, which is not taxed until the wealth is sold (which is different from income, which is taxed as it is earned).

- With the AI boom, those gaps are increasing and likely to expand at an accelerating pace.

- If wealth is taxed, that will require asset sales to pay the taxes, which could pop the bubble.

More specifically:

In the US, the top 10% of households are the well-educated and highly economically productive people who earn about 50% of all income, have about two‐thirds of total wealth, hold about 90% of all equities, and pay about two-thirds of federal income taxes, with all of these numbers growing at a good pace. In other words, they are doing great and contributing a lot.

In contrast, the bottom 60% are not well-educated (e.g., 60% of all Americans have below a sixth-grade reading level), relatively unproductive economically, and combined earn just about 30% of all income, own only 5% of all wealth, own only about 5% of all equities, and pay under 5% of all federal taxes. Their wealth and economic prospects are relatively stagnant, so they are squeezed financially.

Naturally, there is great pressure to tax and redistribute the wealth and money from those in the top 10% to those in the bottom 60%.

While we never had wealth taxes, there is now a lot of pressure to have them at both the state and federal level. Why tax wealth now when it wasn’t taxed before? Because that’s where the money is—i.e., because most of those at the top are getting richer through their wealth increases, which aren’t taxed, rather than through their earned income.

Wealth taxes have three big problems:

- The rich can move, and if they move, they take their talents, productivity, income, wealth, and tax paying with them, reducing them in the places they leave and boosting them in the places they go to;

- they are difficult to implement (for reasons you probably know and don’t want me to digress into because this note is already too long); and

- they take money away from the investments that finance the productivity-gaining activities to give it to the government under the unlikely assumption that they will handle it well to make those in the bottom 60% productive and prosperous.

For these reasons, I would much prefer to see a tolerable tax (e.g., a 5-10% tax) on unrealized capital gains. But that’s another subject for another time.

P.S. So How Would a Wealth Tax Work?

In a future note, I will address this issue more completely. Suffice it to say that the US household balance sheets show roughly $150 trillion of gross wealth, but less than $5 trillion is in cash or deposits. So, if a 1-2% annual wealth tax were imposed, the cash requirement would exceed $1-2 trillion per year—while the liquid cash pool is not much larger than that.

Anything like that would pop the bubble and lead to a bust. Of course, wealth taxes wouldn’t be levied on all people; they would be levied on the rich. I won’t get into the numbers now, as this piece has gone on long enough. Suffice it to say that wealth taxes would 1) trigger a forced selling of private and public equity, depressing valuations; 2) increase credit demand, potentially inflating borrowing costs for the wealthy and for markets generally; and 3) encourage offshoring or relocation of wealth to friendlier jurisdictions. These pressures become acute if governments impose wealth taxes on unrealized gains or illiquid assets such as private equity, venture holdings, or even concentrated public equity positions.

Disclaimer:

- This article is reprinted from [raydalio]. All copyrights belong to the original author [raydalio]. If there are objections to this reprint, please contact the Gate Learn team, and they will handle it promptly.

- Liability Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not constitute any investment advice.

- Translations of the article into other languages are done by the Gate Learn team. Unless mentioned, copying, distributing, or plagiarizing the translated articles is prohibited.

Related Articles

Reflections on Ethereum Governance Following the 3074 Saga

Gate Research: 2024 Cryptocurrency Market Review and 2025 Trend Forecast

Gate Research: BTC Breaks $100K Milestone, November Crypto Trading Volume Exceeds $10 Trillion For First Time

NFTs and Memecoins in Last vs Current Bull Markets

Altseason 2025: Narrative Rotation and Capital Restructuring in an Atypical Bull Market