Decentralization without sacrificing commercial viability, a symbiotic solution from the perspective of balancing power

Many of us feel uneasy about Big Business. We enjoy the products and services corporations offer, but we’re wary of trillion-dollar monopolies, closed ecosystems, video games that border on gambling, and companies that manipulate governments for profit.

We also fear Big Government. We need police and courts to maintain order, and we rely on government for essential public services. Yet we resent when governments arbitrarily choose winners and losers, restrict freedom of speech, reading, or thought, and especially when they violate human rights or start wars.

There’s a third force in this triangle: the Big Mob. We value independent civil society, charities, and platforms like Wikipedia, but we dislike mob justice, cancel culture, and extreme events like the French Revolution or the Taiping Rebellion.

At heart, we all want progress—whether technological, economic, or cultural—but we also fear the three core forces that have historically driven it.

One common solution is the concept of balanced power. If society needs strong forces to drive development, those forces should keep each other in check—either through internal competition (such as among businesses) or through checks and balances between different powers, ideally both.

Historically, these balances often emerged naturally: geography and the challenges of coordinating large groups for global tasks created “diseconomies of scale,” which limited the concentration of power. In the 21st century, that’s changed—these three forces are growing stronger and interacting more frequently than ever.

This article explores these dynamics and offers strategies to protect the increasingly fragile balance of power in our world.

In a previous post, I described this new world—where “Big X” forces persist in every domain—as a “dense jungle.”

Why We Fear Big Government

Fear of government is not unfounded: governments possess coercive power and can harm individuals. Their destructive capacity far exceeds anything Mark Zuckerberg or crypto professionals could ever wield. For centuries, liberal political theory has focused on “taming the leviathan”—how to enjoy the benefits of law and order without falling prey to unchecked monarchical rule.

(Taming the leviathan: In political science, this means using rule of law, separation of powers, and decentralization to constrain the public authority that could infringe on individual rights. The goal is to maintain order while preventing abuse and balancing public order with personal freedom.)

This theory boils down to one principle: government should be the “rule maker,” not a “player.” In other words, government should act as a reliable “arena” for resolving disputes within its jurisdiction, not as an active participant pursuing its own goals.

There are several ways to achieve this ideal:

- Libertarianism: Government rules should be limited to three—no fraud, no theft, no murder.

- Hayekian Liberalism: Avoid central planning; if intervention is needed, set clear goals and let the market determine how to achieve them.

- Civil Libertarianism: Protect freedom of speech, religion, and association; prevent government from imposing its cultural or ideological preferences.

- Rule of Law: Government should legislate clear “do’s and don’ts,” with courts enforcing the law.

- Supremacy of Common Law: Abolish legislative bodies and let decentralized courts set legal precedents case by case.

- Separation of Powers: Divide government authority among branches that keep each other in check.

- Subsidiarity Principle: Assign problems to the lowest competent authority to minimize concentration of decision-making power.

- Multipolarity: At the very least, prevent any single nation from dominating the world; ideally, also ensure:

- No country becomes overly dominant in its region;

- Every individual has multiple fallback options to choose from.

Similar logic applies even in governments not traditionally considered “liberal.” Recent research shows that institutionalized authoritarian governments often drive economic growth more effectively than personalized ones.

Still, it’s not always possible to keep government from becoming a “player,” especially during external conflicts—when participants challenge the rules, the participants win. Even then, government power is usually strictly limited, as in the Roman “dictator” system: dictators had extraordinary authority during emergencies but relinquished it when the crisis ended.

Why We Fear Big Business

Business criticism falls into two main categories:

- Businesses are bad because they’re “evil”;

- Businesses are bad because they’re “lifeless.”

The first (“evil”) stems from the fact that companies are highly efficient goal-optimizing machines. As their capabilities and scale grow, the goal of maximizing profit diverges more from the interests of users and society. This pattern is clear across many industries: sectors often start with passionate hobbyists, but over time, profit becomes the primary focus and user interests suffer. For example:

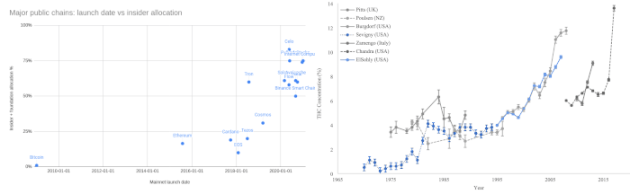

Left: Share of newly issued crypto tokens allocated to insiders (2009–2021); Right: THC concentration in cannabis (1970–2020).

The video game industry shows the same trend: once focused on fun and achievement, it now relies on “slot machine” mechanics to maximize player spending. Even major prediction markets are shifting away from social good and toward sports betting.

These cases result from increased corporate capability and competitive pressure. Another set of problems arises directly from scale: the bigger the company, the more it can distort its environment—economically, politically, or culturally—for its own benefit. A company ten times larger can reap ten times the rewards from such distortions and acts far more frequently, with far greater resources, than smaller firms.

Mathematically, this mirrors why monopolies set prices above marginal cost, increasing profits at the expense of social welfare: “market price” is the distorted environment, and monopolies manipulate it by restricting supply. The ability to distort is proportional to market share. This logic applies broadly—lobbying, cultural manipulation, and more.

The second problem (“lifelessness”) is that businesses become dull, risk-averse, and homogeneous—internally and across the industry. (Uniform architecture is a classic sign of corporate mediocrity.)

Homogenized architecture is a classic form of corporate blandness.

The word “soulless” is interesting—it sits between “evil” and “lifeless.” It fits companies that “hook users for clicks,” “form cartels to raise prices,” or “pollute rivers,” as well as those that “make cities look identical” or “produce ten formulaic Hollywood movies.”

Both forms of “soullessness” stem from two factors: motivational and institutional homogeneity. All companies are driven by profit; when many powerful actors share the same motivation and lack counterbalances, they inevitably move in the same direction.

Institutional homogeneity comes from scale: the bigger a company gets, the more incentive it has to shape its environment. A $1 billion company invests far more in “environment shaping” than a hundred $10 million firms, and scale also intensifies sameness—Starbucks contributes more to urban homogeneity than a hundred competitors at 1% of its size combined.

Investors can amplify these trends. For a non-sociopathic founder, building a $1 billion company that benefits the world is more rewarding than growing to $5 billion and harming society. But investors are further removed from the non-financial consequences of their decisions: as competition intensifies, those chasing $5 billion get higher returns, while those content with $1 billion get lower (or negative) returns and struggle to attract capital. Investors with stakes in multiple portfolio companies may also inadvertently push those firms toward “merged super-entities.” Both trends are limited by investors’ ability to monitor and hold their companies accountable.

Market competition can ease institutional homogeneity, but whether it offsets motivational homogeneity depends on whether competitors have non-profit-driven motives. Sometimes they do—sharing innovation, adhering to core values, or pursuing aesthetics at the expense of profit—but this isn’t guaranteed.

If motivational and institutional homogeneity make businesses “soulless,” what is a “soul”? In this context, it’s diversity—the non-homogeneous traits that distinguish companies.

Why We Fear the Big Mob

When people praise “civil society”—the part of society that’s neither profit-driven nor governmental—they describe it as “many independent organizations, each focused on different areas.” AI gives similar examples.

But when criticizing “populism,” the image is the opposite: a charismatic leader rallies millions behind a single goal. Populism claims to represent “ordinary people,” but its essence is the illusion of “unified masses”—usually supporting a leader or opposing a hated group.

Even criticisms of civil society focus on its failure to realize “many independent organizations each excelling in their own domain,” instead pushing a spontaneously formed common agenda—such as the phenomenon critiqued by the “Cathedral” theory.

Balance Between Forces

In all these cases, we’ve discussed power balances within each of the three forces. But checks and balances can also exist between different forces, especially between government and business.

Capitalist democracy is a system for balancing the power of Big Government and Big Business: entrepreneurs can challenge government overreach and act independently through capital concentration, while governments regulate businesses.

Palladium-ism celebrates billionaires, but specifically those who “act unconventionally to pursue their unique visions, rather than simply chasing profit.” In this sense, Palladium-ism attempts to “gain the benefits of capitalism while avoiding its pitfalls.”

While both government and markets enabled the Starship project, its ultimate success was driven by neither profit nor government directive.

My views on philanthropy are similar to Palladium-ism. I’ve often advocated for billionaire involvement in charity and hope more will join. But I support philanthropy that “counterbalances other social forces.” Markets rarely fund public goods, and governments often avoid supporting projects that aren’t elite consensus or whose beneficiaries aren’t concentrated in one country. Some initiatives meet both criteria and are neglected by both market and government—wealthy individuals can fill this gap.

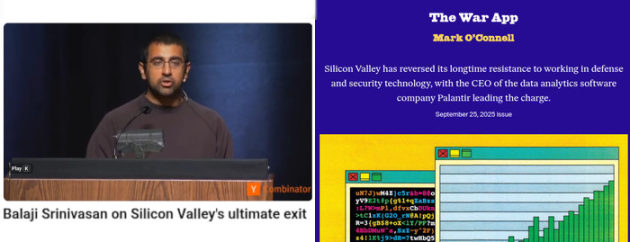

However, billionaire philanthropy can go astray: when it stops balancing government and instead replaces it as the power holder. In recent years, Silicon Valley has seen this shift: powerful tech CEOs and venture capitalists have become less libertarian and supportive of “exit mechanisms,” and instead more directly steer governments toward their preferred goals—in exchange, they make the world’s strongest government even stronger.

I prefer the scene on the left (2013) to the one on the right (2025): the left reflects a balance of power, while the right shows two powerful factions merging instead of counterbalancing.

Power balances can also form between the other two pairs in the triangle. The Enlightenment’s “Fourth Estate” concept positions civil society as a check on government power (even without censorship, governments influence education by funding schools and universities, especially primary education). Meanwhile, media report on corporate activities, and successful businesspeople fund media outlets. As long as there’s no monopoly of power in one direction, these mechanisms strengthen society’s resilience.

Power Balance and Economies of Scale

If you want a theory that explains both America’s rise in the 20th century and China’s development in the 21st, it’s economies of scale. Americans and Chinese often use this to critique Europe: Europe has many small and medium-sized countries with diverse cultures, languages, and institutions, making it hard to foster continent-wide giants; in a large, culturally homogeneous nation, companies can easily scale to hundreds of millions of users.

Economies of scale are crucial. Humanity needs scale—it’s the most effective driver of progress. But it’s a double-edged sword: if my resources are twice yours, my progress will be more than double; next year, my resources might be 2.02 times yours. Over time, the strongest actors control everything.

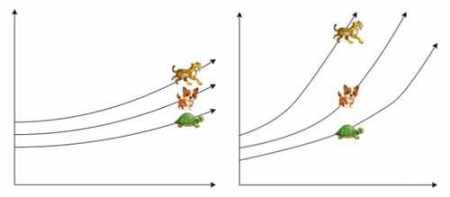

Left: Proportional growth—small initial gaps remain small; Right: Growth under economies of scale—small gaps widen dramatically over time.

Historically, two forces offset economies of scale and prevent power monopolies:

- Diseconomies of scale: Large organizations are inefficient—internal conflicts, communication costs, and geographic distance.

- Diffusion effects: People moving between companies or countries carry ideas and skills; developing nations catch up by trading with advanced ones; industrial espionage spreads innovation; companies use one social network to drive traffic to another.

If the “scale leader” is a cheetah and the “scale laggard” a turtle, diseconomies slow the cheetah, while diffusion pulls the turtle closer. Recently, several forces have shifted this balance:

- Rapid technological advancement: Makes the “super-exponential growth curve” of scale steeper than ever.

- Automation: Enables global tasks with minimal manpower, drastically reducing coordination costs.

- Proliferation of proprietary technologies: Modern society can produce software and hardware that are “open for use but closed for modification and control.” Historically, delivering products meant allowing inspection and reverse engineering—but today, that’s no longer true.

Economies of scale are growing stronger: while the internet may broaden “idea diffusion,” “control diffusion” is weaker than ever.

The core dilemma: In the 21st century, how do we achieve rapid progress and build prosperous civilizations without extreme concentration of power?

Solution: Force greater diffusion.

What does “forcing greater diffusion” mean? Let’s start with some government policy examples:

- EU’s mandatory standardization (such as USB-C): makes it harder to build “proprietary ecosystems incompatible with other technologies.”

- China’s compulsory technology transfer policy.

- US ban on non-compete agreements: I support this, as it forces partial “open-sourcing” of tacit knowledge—when employees leave, they can apply skills learned elsewhere, benefiting more people. NDAs may restrict this, but enforcement is spotty.

- Copyleft licenses (like GPL): require any software based on Copyleft code to remain open source and under Copyleft terms.

We can expand further: governments could emulate the EU’s carbon border adjustment and create a new tax—levying based on a product’s “degree of proprietariness,” domestically and internationally; if a company shares technology with society (including open source), the tax rate drops to zero. Another idea worth reviving is the “Harberger tax on intellectual property”—taxing IP at its self-assessed value to incentivize efficient use.

We should also adopt a more flexible strategy: adversarial interoperability.

As Cory Doctorow (sci-fi author, blogger, and journalist) explains:

“Adversarial interoperability means developing new products and services that connect with existing ones without the manufacturer’s permission. Examples include third-party printer ink, alternative app stores, or independent repair shops using compatible parts from competitors.”

Essentially, this strategy is “interacting with tech platforms, social media sites, companies, and governments without permission, while benefiting from the value they create.”

Examples include:

- Alternative clients for social media platforms: users can view and post content, and choose their own content filtering.

- Browser extensions with similar functions: like ad blockers but targeting AI-generated content on platforms such as X.

- Decentralized, censorship-resistant exchanges between fiat and crypto: mitigating the “chokepoint risk” of centralized financial systems (single points of failure that can cripple the whole system).

In Web2, much value extraction occurs at the user interface layer. If alternative interfaces can interoperate with platforms and other users, people can stay in the ecosystem while avoiding the platform’s value capture.

Sci-Hub is a prime example of “forced diffusion”—it’s advanced fairness and open access in science.

A third strategy to enhance diffusion is to revisit Glen Weyl and Audrey Tang’s “plurality” concept. They describe it as “enabling collaboration across differences”—helping people with diverse views and goals communicate and cooperate, enjoying the efficiency of large groups while avoiding the pitfalls of single-goal-driven entities. This helps open-source communities, alliances of nations, and other non-monolithic groups increase their “diffusion level,” so they can share scale benefits while staying competitive with centralized giants.

This approach is structurally similar to Piketty’s “r > g” theory and his call for a global wealth tax to address wealth concentration. The key difference: we’re focused not on wealth itself, but on its upstream source—the root of unconstrained wealth concentration. What we aim to diffuse is not money, but the means of production.

I believe this is superior for two reasons: first, it directly targets the dangerous core—the combination of extreme growth and exclusivity—and, if done well, can even boost overall efficiency; second, it isn’t limited to one form of power—a global wealth tax may curb billionaire dominance, but can’t restrain authoritarian governments or transnational entities. By “forcing global decentralization and technology diffusion”—making it clear: “either grow with us and share core tech and network resources at a reasonable pace, or develop in isolation and be excluded”—we can more comprehensively address power concentration.

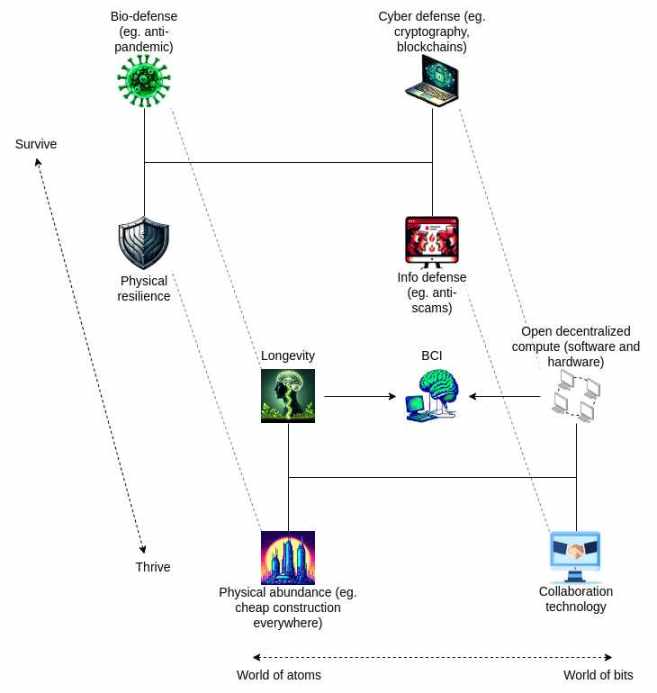

D/acc: Making a Multipolar World Safer

Pluralism faces a theoretical risk—the “fragile world hypothesis”: as technology advances, more actors may gain the ability to inflict catastrophic harm on humanity; the less coordination there is, the higher the chance one will choose to do so. Some argue the only solution is further centralization, but this article advocates the opposite—less concentration of power.

D/acc (Defensive Accelerationism) is a complementary strategy that makes decentralization safer. Its core is to develop defensive technologies in step with offensive ones, and these defenses must be open and accessible to all—reducing the urge to centralize power out of security fears.

D/acc technology cube diagram

The Morality of Pluralism

The morality of the slave says: you are not allowed to become strong.

The morality of the master says: you must become strong.

The morality centered on power balance says: you must not become a hegemon, but you should strive for positive impact and empower others.

This idea is a modern interpretation of the centuries-old distinction between empowerment and control.

To “have empowerment without control,” there are two paths: maintain high diffusion to the outside world, and design systems to minimize their potential as levers of power.

In the Ethereum ecosystem, the decentralized staking pool Lido is a good example. Lido manages about 24% of all staked ETH, but concerns about it are much lower than for any other entity with equal control. That’s because Lido isn’t a single actor—it’s a decentralized DAO with dozens of node operators and a dual governance model, where ETH stakers have veto power. Lido’s efforts here are commendable. Of course, the Ethereum community is clear: even with these safeguards, Lido should not control all ETH staking—and for now, it’s far from that risk threshold.

Going forward, more projects should consider two key questions: not just how to design a business model to acquire resources, but also how to design a decentralization model to avoid becoming a node of concentrated power and to address the risks that come with power.

In some cases, decentralization is easy: few worry about English’s dominance or the widespread use of open protocols like TCP, IP, or HTTP. In others, decentralization is challenging—some applications require actors with clear intent and agency. Balancing flexibility against the risks of concentration will be an ongoing challenge.

Special thanks to Gabriel Alfour, Audrey Tang, and Ahmed Gatnash for their feedback and review.

Statement:

- This article is republished from Foresight News. Copyright belongs to the original author Vitalik Buterin. If you have concerns about this republication, please contact the Gate Learn team, which will address the issue promptly according to relevant procedures.

- Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not constitute investment advice.

- Other language versions are translated by the Gate Learn team. Unless Gate is mentioned, do not copy, distribute, or plagiarize translated articles.

Related Articles

The Future of Cross-Chain Bridges: Full-Chain Interoperability Becomes Inevitable, Liquidity Bridges Will Decline

Solana Need L2s And Appchains?

Sui: How are users leveraging its speed, security, & scalability?

Navigating the Zero Knowledge Landscape

What is Tronscan and How Can You Use it in 2025?